![Item #17305 J.D. Salinger His Guiding Philosophy: “It’s a tremendously tall order, an undertaking seemingly more beautiful and more real in the mind’s eye than in actual practice [...] The taoist feat is to know at all times that there is nothing that isn’t shit-- but also, and more difficult, nothing that is.”. J. D. Salinger.](https://maxrambod.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/17305.png?width=768&height=1000&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1698799257)

J.D. Salinger His Guiding Philosophy: “It’s a tremendously tall order, an undertaking seemingly more beautiful and more real in the mind’s eye than in actual practice [...] The taoist feat is to know at all times that there is nothing that isn’t shit-- but also, and more difficult, nothing that is.”

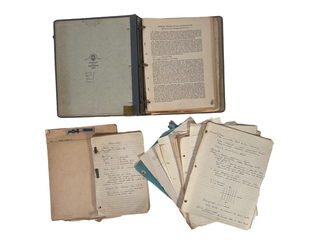

TLS - Typed Letter Signed

Salinger, J.D. American author of Catcher in the Rye. Two typed letters, one signed “Jerry” and the other signed “JDS”. June 17, 1978 (two pages) and December 10, 1971 (one page). To Eileen Paddison, a close friend and aspiring writer who maintained a correspondence with Salinger for over 15 years. An archive revealing the Taoist philosophical underpinnings of Saliner’s iconic critique of the American bourgeois life-style. In 1977, Gerald Rosen authored an entire book on the Zen and Buddhism influence on Salinger work, Zen in the Art of J. D. Salinger, analyzing Buddhism concepts and phrasing in The Catcher in the Rye, Franny & Zooey, and also his other short stories. In these letters, Salinger goes into detail about exactly what it is in Taoist practice he finds so compelling.American Author J.D. Salinger built his canon with novels starring hungry young truth-seekers, dissatisfied with the materialism and soullessness of upper middle-class American life. He was intensely averse to the fame that met his work, refusing to do the usual press-circuit. Therefore, it’s personal letters like these which can give us a window into the philosophy behind famous works like Catcher in the Rye, Nine Stories, and Franny and Zooey. Salinger begins the 1978 letter by imploring Eileen to “See me as I am, a cluttered man-- writer, parent, chauffeur, cook, snow-remover, unreliable letter writer” and states further that “If I’m to be liked, at all, I think I’m best liked only slightly or intermittently.” Another descriptor for that list: Taoist. Salinger’s intense devotion to honesty and truth, and his extreme aversion to anything “phony”, made the neutral balance of Taoism something aspirational and extremely challenging: “You say you certainly haven’t been living Taoism. You know, of course, that it’s no easy way to live. Probably Lao-tse and Chaang-tse themselves were better at writing about it than living it.” Salinger craved the kind of relief from artifice that Taoist belief promises, but doubted it could really be experienced: “It’s a tremendously tall order, an undertaking seemingly more beautiful and more real in the mind’s eye than in actual practice. The task, I think, is to stay close to Taoism in affection, if not in practice, at all times, for life. It’s possible, probably, that an effort should be made to screen most of the things that happen to oneself through Taoist thought. I know that I usually fall into a kind of unhappiness, depression, If I let my complicated daily life alienate me too far from Taoist values and non-values.” Finally, Salinger writes about what it is exactly in taoism that’s so compelling and so difficult for him; namely, relief from the need to evaluate what’s authentic or not, but to simply live inherently free of pretentiousness or falsity: The taoist feat is to know at all times that there is nothing that isn’t shit-- but also, and more difficult, nothing that is. To hold those mutually eliminating realities in the head at the same time, and yet not (by some small miracle that is no miracle at all) allow them to eliminate each other.” These ideas are rooted deeply n Salinger’s personal life as well as his writing. Seven years earlier, in his letter from 1971, Salinger writes that there is “probably no richer or better stuff in all of Eastern philosophy” than taoism. His scholarship is obvious here-- he mentions a preferred translation by Legge, calling it “the very heart of Zen Buddhism [...] “what marvelous things, thoughts, all of them” and admits that though “there’s something wrong in sticking to one subject for too long [...] the Tao itself, though, is the kind of subject that stands outside thinking and non-thinking, and so is a sort of exception....” As to the question of whether Taoist Buddhism actually impacted Salinger’s most famous novels, starting with The Catcher in the Rye published 20 years earlier, Salinger’s discussion here in this letter makes clear beyond a doubt that Eastern philosophy has guided him for at least that long: “Taoist passivity. An enormous subject, and one I’ve been pondering, off and on, for more years than you’ve been alive. The very word “Tao” is an excitement.”

Both on the author’s usual goldenrod paper. Original mailing envelope bearing his PO Box address in Windsor, Vermont, the usual mailing address he preferred while writing from his home in Cornish, New Hampshire. A philosophical letter with important content for the interpretation of Salinger’s novels, in near fine condition. .

Item #17305

Price: $12,000.00

See all items by J. D. Salinger